Space Shuttle Launch Complex 39-B Construction Photos

Page 5

GOX Arm Strongback Lift 1 (Original Scan)

FSS Swingarm Strongback lift.

This strongback supported the hinges for the GOX arm.

Additional commentary below the image.

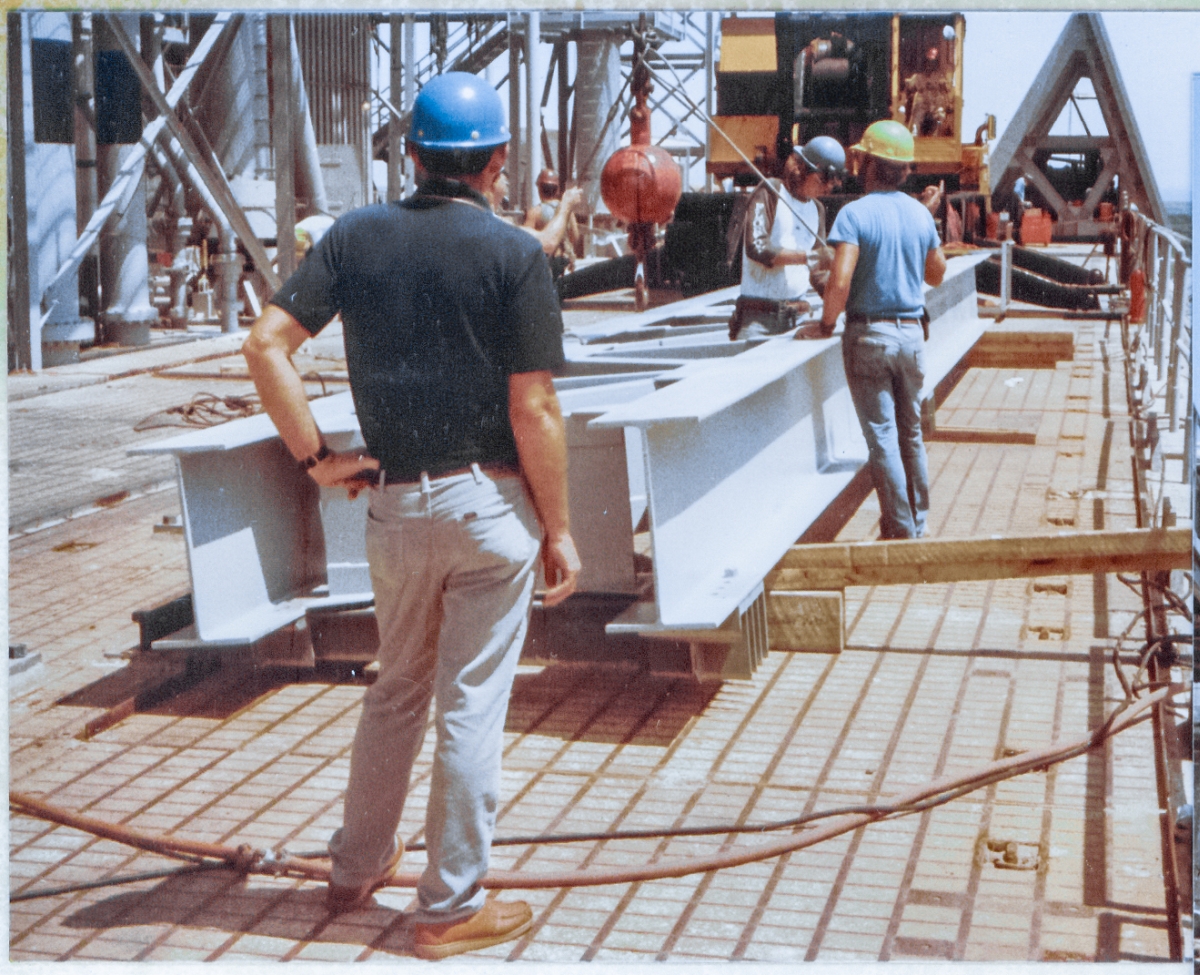

Top Left: (Reduced)

Ok, another lift. Same players as before. There's Wade Ivey, closest to us, with a blue hard hat, and Rink Chiles is wearing a yellow one. Not certain of the name of the guy standing inside the trusswork of the strongback who's finishing up with tying the lifting sling to the strongback, but it might be Rink's brother Ruben. Rink was not to be fucked with. Ruben... even more so.

There's a lot going on here that would never catch your eye, unless I draw your attention to it (you're already nice and zoomed in, in another tab, right?), so let's start with Rink, and the fact that he's staring directly at the place where the lifting sling they're attaching to the strongback is tied back to the crane line. Seriously, get a look at that thing, ok?

What. The. Fuck?

They're working with some god-awful contrapted conglameration of shackles and wire rope, and the whole schmutz is tying on, above the headache ball(!) and they're ignoring the hook(!) beneath that headache ball.

This is some seriously non-standard procedure, and you will soon find out what the hell's going on with it, and why they're doing it, and how it will serve as a demonstration of the absolute mastery of their craft, that Wade and Rink both possess, as practiced by adepts who know the rules better than the people who wrote the rules, and who further know exactly when, where, and how, to break those rules in a way that cuts through bullshit and wasted energy with maximum efficiency and elegance, not caring in the slightest about how things look, but instead zeroing in with a surgeon's precision on how things work, to the exclusion of all else.

But really, above the headache ball? C'mon, you gotta be kidding me. We'll return to this fuckery here in a bit, but let's look around some more, first, ok?

This strongback will be supporting the GOX (Gaseous OXygen, as opposed to Liquid OXygen) arm hinges (and therefore the weight of the entire gox arm itself whenever it was in use), instead of the gox arm latchback which only bore part of the weight of the gox arm, when it was not in use, and was retracted back flush against the face of the FSS, and locked safely out of the way into position on that latchback.

Compared to the FSS upon which it lived, the gox arm wasn't much, but it was still, in and of itself, a pretty substantial steel structure, complete with a bunch of plumbing and crap, and it also moved in a couple of different ways, and the loads incurred as it moved and as it hit the stops at either end of its range of travel, were sufficient that they needed to distribute the combined loads along enough vertical platforming extent of the FSS to keep from bending or breaking something on the FSS as well as keeping the gox arm itself sufficiently straight, level, and true, so as it might be prevented from... oh, I dunno, maybe smashing into the External Tank and blowing the whole place clear to hell in a glowing cloud of molten drops of liquid steel, perhaps. When you're launching expensive national assets like the Space Shuttle, you do not want other things like gox arms to come falling down on top of them from above. And so, you get strongbacks to help carry and distribute those loads, and see to it that the goddamned gox arm stays right where you originally put it, as you intended.

The FSS was originally part of the LUT (Launch Umbilical Tower), which they cut up and re-used, and as such it required many substantial modifications to turn it in to a proper Fixed Service Structure, and the gox arm with its attendant strongback was only one of those many modifications.

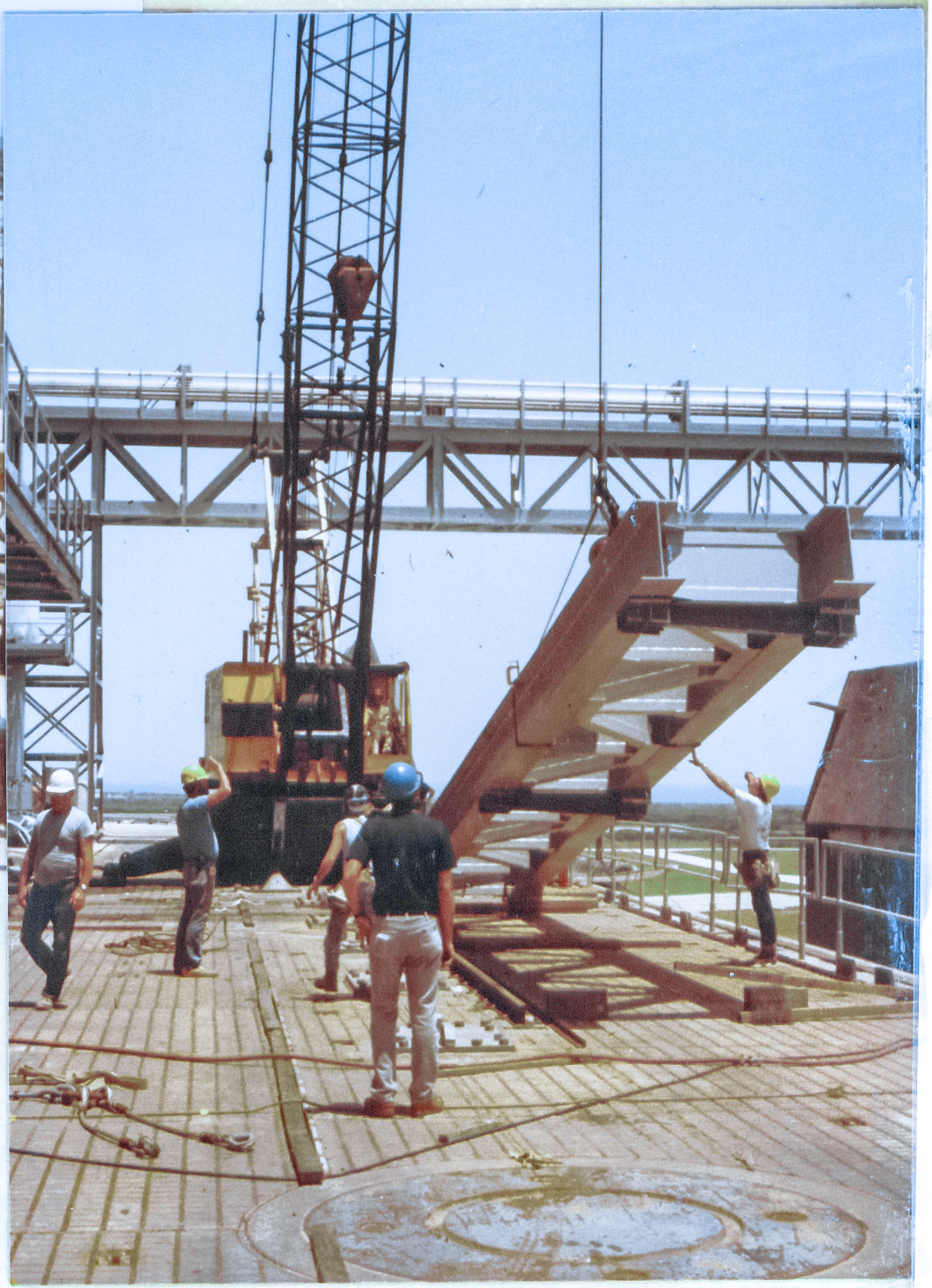

In the background, the curiously-triangular shape of one of the SFD's (Side Flame Deflector), can be seen, looking down along it, lengthwise. There was another one, over on the other side of the flame trench, that matched it, and they were both installed because the footprint of the Space Shuttle's SRB's was wider than the footprint of the five F-1 engines on the bottom of a Saturn V, for which pads 39-A and 39-B were both originally designed and built. That wider footprint brought the very edge of the hellish torrent of flame the SRB's spouted at liftoff directly into conflict with the edges of the flame trench, which were never intended to endure such a thing, nevermind the adjoining equipment nearby on the pad deck which that hellish torrent of flame would splash directly into, and so they came up with the SFD's, (which could be rolled back and forth on rails, to keep them out of the way when they weren't in use, and yes sometimes it seemed like the whole world out there was movable in some way to keep it out of the way when not in use) as a method of keeping that hellish torrent of flame down inside the fucking flame trench, where it belonged.

Also, take a look at the ground that Wade Ivey is standing on. This image offers a good look at the transverse steel reinforcing that interesects the longitudinal steel reinforcing for the concrete which the tracks of the fully-loaded crawler bear directly down upon, when it's carrying its burden across the pad deck, which I mentioned earlier, in the bottom paragraph, here.

That might be the yellow cab of a 90-ton P&H crane back there, but maybe not. Memory is not to be trusted on that one. Cranes are rated in funny ways, and one of the things you can't do with a 90-ton crane, is pick up 90 tons. Except under very special and never-to-be-seen-on-a-normal-job-site conditions.

Imagine that. Who knew?

Top Right: (Full-size)

Ok, now we're moving. And again, at high zoom, get a look at where the lifting sling is coming into the crane line, and marvel at the goinked-up condition of the last little bit of things, along with the (mostly, but not quite fully, hidden) headache ball, waaay off center, and it's for sure as hell they're not using the goddamned hook now, and what the fuck is going on here, anyway?

Disregarding goinked-up headache ball, we can now get a pretty good look at the "underside" of the strongback, which will be in contact with the FSS when it's hung, and can clearly see the top two weldments where the connection will occur. The strongback spanned the height of two full FSS platform levels, and the connections would perforce be made on the structural steel framing of those platform levels, which makes for three connection points (stop and think about that one for a minute if you need to, because it's how things in the real world work, and it's useful to know stuff like this) and since the platform levels on the FSS were in twenty-foot increments, the overall length of our strongback will be a bit over 40 feet. Certainly not as big as the Eiffel Tower, but equally certainly not something you'd want to drop on your big toe. Notice please, when looking closely at those (darker gray) weldments, that the whole strongback will be slightly tilted with respect to the nice flat face of the FSS. Interesting, hmm? Well, it's interesting to me, even if it's not interesting to you. There's a story there, and maybe I'll tell it to you later, and maybe I won't. We'll just have to wait and see.

Rink is using hand-signals to tell the crane operator what to do, and the crane operator is doing exactly what he's being told to do, and a pretty hefty goddamned hunk of cold lifeless steel is about to break contact with the surface of the earth, and everybody's life is now held in Rink and the crane operator's hands (as well as the hands of the ironworkers who constructed and fastened that outré lifting sling to the strongback), and I'm guessing that you've probably never done all so very much in your life that involved such a brutally pass or fail level of trust in your coworkers, have you?

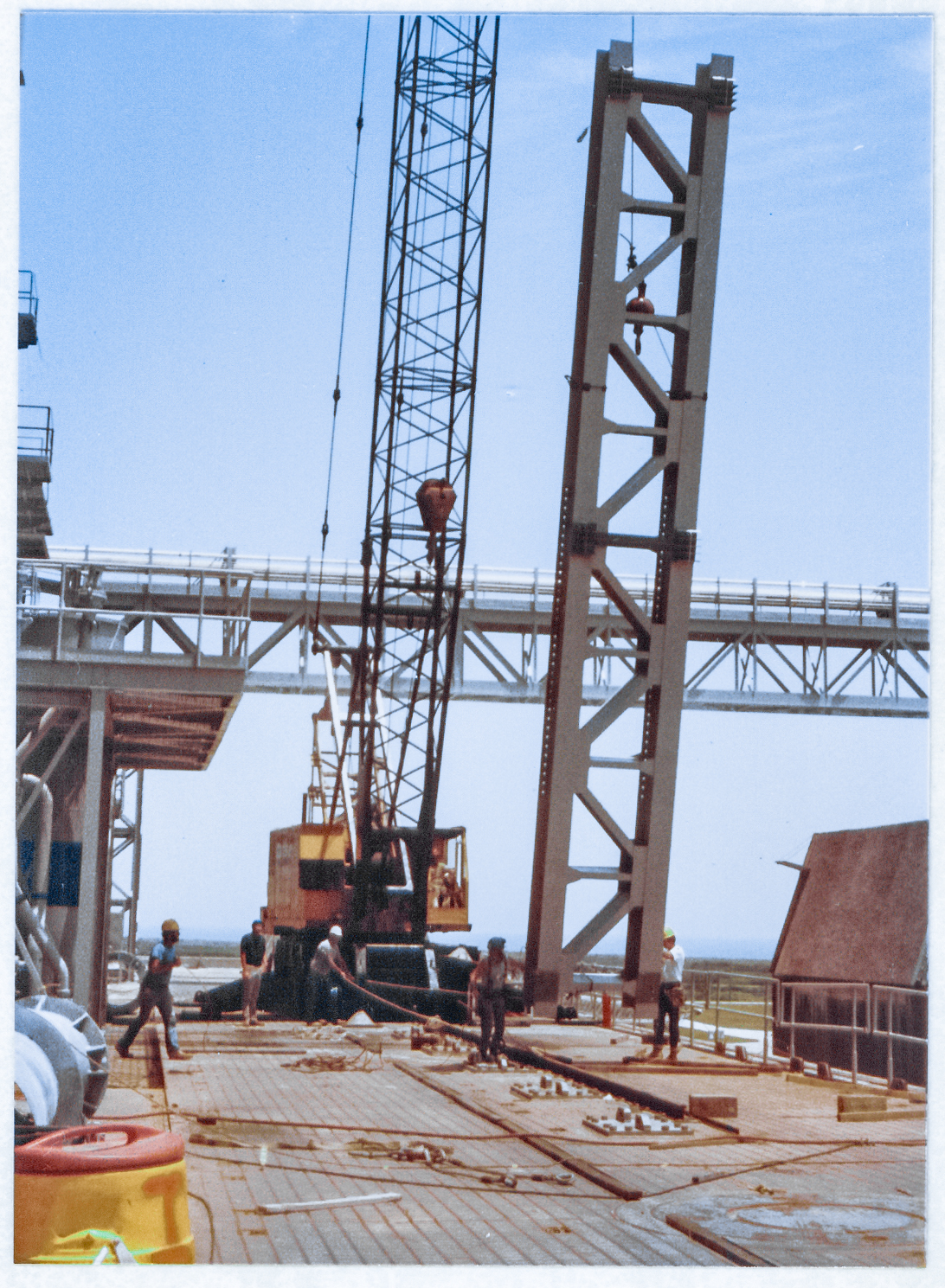

Bottom Left: (Full-size)

Well, we're up in the air now, in suspension, whack-ass headache ball and all, and whatever's going to happen is what's going to happen, and these guys wouldn't be standing around here if they thought that whatever's going to happen was going to be bad, but still.....

Over on the far right, down near the bottom of the frame, the face of the other SFD can be seen, across the yawning gulf of the flame trench. The handrail keeping people from stepping into that particular hole looks wonky, and it is, because it's removable. Has to come out and go away before the SFD can be rolled into its launch position. Removable handrail is even less trustworthy than fixed handrail, 'cause it wiggles around in its sockets, and if you lean up against it, it can suddenly move and if it suddenly moves and you're not expecting it to, it just might throw you and if it throws you to the wrong place, well then, that could turn out pretty bad, couldn't it?

On the SFD itself, a float can be seen in silhouette against the sky, up near the top. Work was being done over there, but I do not recall exactly what, unfortunately. At one point along the way, we had to modify the edge of the SFD, and then emplace Fondu Fyre along a narrow strip, but I'm not sure if this is part of that, or not. The deflector looks just a little too clean and neat for me to believe that particular work-effort was ongoing when this photograph was taken. Unless, by purest chance, this was at the very beginning of that work, before anything sensible had been done, above and beyond the business of getting mobilized to perform the work. It's possible, but I'm still not convinced.

Also, please note that the lowest area where our strongback will be connected to the FSS does not seem to have any weldment and instead appears to be simply two squarish areas with darker paint on them. Clearly, whatever's going to do the work of being the connection point is already up there somewhere on the FSS, in place, waiting for the strongback to show up so they can finish things off. Weency teency little details. Launch pads are loaded with weency teency little details, and every last one of 'em tells a story, and it's very important to know what that story is when you're working on them, or otherwise you're gonna go broke. Bidding this kind of work is a meticulous and time-consuming business, and you'd better not miss anything, or woe unto you and the company you just might bankrupt with your mindless oversight. There are stories.

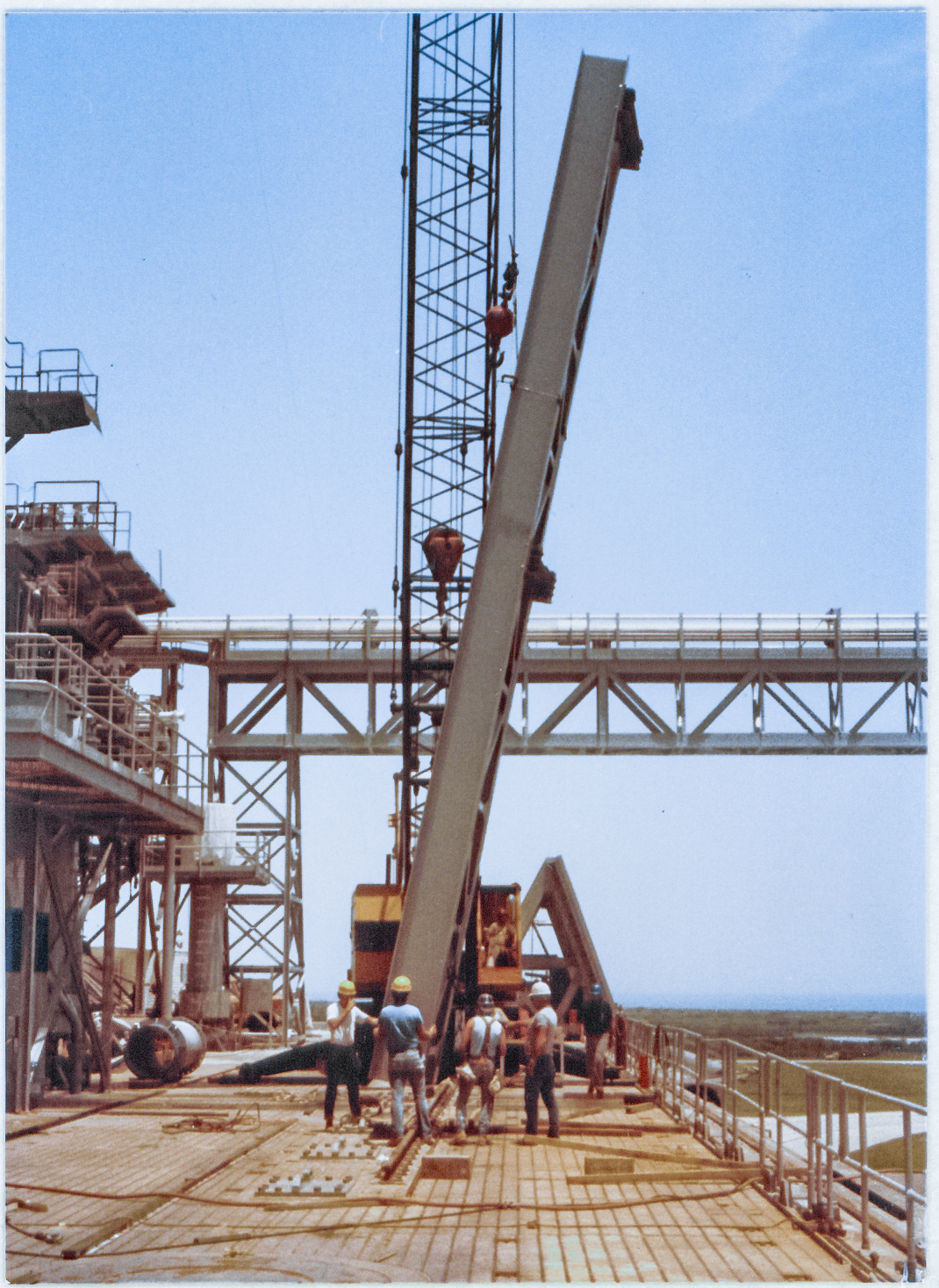

Bottom Right: (Full-size)

And now the strongback has been rotated around, just about exactly opposite to the orientation it will take when it's bolted on to the FSS, and it's being given one hell of a lot of attention and close-looking-at by Wade, and Rink, and everybody else, and we're going to be going up here pretty soon, once every last one of these people who are looking at this thing with expert eyes have become comfortable with the looks of things, and not one minute before. But wouldja just look at that fucking headache ball and hook?!? I mean really. I mean, what the fuck? Really.

And..... we're now getting an excellent look at the fact that they've chosen a most peculiar attach point on the strongback for their lifting sling. They're not lifting it from the top, as was done with the OMBUU, and as is done with just about every single lift of this type you'll ever encounter in your life. No, not at all. They've attached their lifting sling almost a full third of the length of the strongback, down from the top. They're so far down from the top in fact, that the strongback has become tilted at an unsettling angle from the vertical, and it looks like if they'd gone much further down, they would begin risking the thing tipping waaay over, to near horizontal. It has to attach to the FSS vertically, and yet they're way off-vertical with it right now, and I'm guessing that the particulars of the existing off-vertical orientation, along with the way the strongback will encounter the FSS and transition from leaning way over to standing straight up as it must, in order to connect it to the FSS, and/or any inclination for the strongback to tip or roll even farther off vertical might be some of the things that are getting such a close going-over by everyone right now, but why? Curiouser and curiouser.

Elsewhere, while you're at it, get a look at the grass, and concrete, and scenery, and the distant ocean, back there, through and above the wonky removable handrail, and this image will help you a little further along with your appreciation of the vast size of things out on the pad. We're not even up on the tower, but clearly we're a pretty good ways up in the air, already. Yeah, the place is pretty big.

Behind the strongback, and the crane, the north piping bridge looks perfectly fine, and I suppose it goddamned good and well oughtta be perfectly fine, considering the horseshit treatment NASA gave us over the motherfucker, back when we fabricated and delivered it, and yes, I'm still pissed off about that one, all these years later. Assholes.

Addendum 2017 07 11:

One of my interlocutors (Hi Manfred!), has drawn my attention to a couple of points that I did not address specifically, above, so I suppose I'll get on that right now.

Regarding the "thinness" of the lifting sling, and the apparent, possibly quite dangerous, mismatch between its thread-like appearance, and the obvious substantial weight of the strongback, I shall quote one of the grizzled old ironworker foremen I knew back in my Sheffield Steel days, who worked for Wilhoit, and who, when the subject of an inch-square piece of steel came up for some damn goofy reason or other, said "You can pick up the world with an inch of steel." Thank you Elmo McBee, for that little quote which has stayed with me for a lifetime. Steel is STRONG. A whole lot stronger than people tend to think it is. Especially in tension as it is with this thread-like lifting sling and the load it is so very comfortably bearing.

And if you don't believe me, well then, here's a quote from the Wilkof Wire Rope Cable Materials Guide that I found with a single click, Googling for "improved plow steel" (gotta love the lingo in this work, don'tcha?).

Improved Plow Steel

Plow steels are a high-strength steel which contain between 0.5 and 0.95 percent carbon. Improved Plow Steel (IPS) is one of the best grades of wire ropes available. It's strong, more durable and wear-resistant than normal plow steel. This type of steel has a tensile strength of 1,770 Newton per square millimeter, or roughly 260,000 pounds per square inch.

Extra Improved Plow Steel

Extra Improved Plow Steel (EIPS) has a minimum breaking strength 15 percent higher than Improved Plow Steel. It's typically used in wire ropes for applications that require maximum rope strength, such as mine shaft hoisting. This type of steel has a tensile strength of 1,960 Newton per square millimeter, or about 285,000 pounds per square inch.

Get a load of those numbers, how 'bout? These are numbers for ONE SQUARE INCH. These would be the numbers for Elmo McBee's "inch of steel."

Over TWO HUNDRED AND FIFTY THOUSAND POUNDS before you break the sonofabitch.

Damn.... I mean like, damn!

And in addition to the bare strength of the material, as regards the fact that the goddamned lifting sling is restrained from unexpectedly breaking loose and sliding along the strongback, with potentially very catastrophic results, by nothing more than a common C-clamp, yes, that's exactly how they do it. Choker slings, by virtue of the the they way they grip their loads, exert a powerful gripping force upon that load, and that gripping force only gets stronger and stronger as the load gets heavier and heavier. A awful lot of iron goes up into the air with just the choker sling and no C-clamp at all.

In this instance, the C-clamp might be taking a little loading, but that's only because of the fucking nightmare "three coat system" of paint that was used on this project, spec'd out by KSC-STD-C-0001 (which was eventually shitcanned and replaced by NASA-STD-5008 which itself sadly constitutes no real improvement in dealing with the real-world aspects of things) with with a psychotically slick exterior surface of Aliphatic Polyurethane, which would be doing its best to unsafely counteract the very sensible gripping effects of the choker sling thus causing it to lose its grip and slide, and which had to be accounted for at all times, and which was a huge pain in the ass, and which never did serve to do the job which it was purported to do, forcing NASA to periodically sandblast and repaint everything despite the marvelous and well-advertised wonderful effects of their damnable three-coat-system, none of which actually worked worth a shit out in the beachside salt air of the launch pads, and good godDAMN but did I ever hate that sonofabitch three-coat-system and all the lethally stupid pricks who implemented it to crazed degrees of lunacy having nothing whatsoever to do with actual corrosion control and instead everything to do with simply fucking with people and attempting to lard on as much pointless additional costs and work delays as inhumanly possible for the sheer malicious pleasure of it.

But nobody got killed this day.

We were being careful.

We already knew about the deadly side-effects of NASA's pointlessly-deranged and useless three-coat corrosion-control system.

And we took them into account, ahead of time.

Addendum 2019 08 21:

It's now been well over thirty years since this picture was taken, and a lot has happened over the course of that span of time. The Space Shuttle program is no more, and they're now working on SLS, which will be a proper Saturn V class launch vehicle, which they're planning on taking people to the moon with, one day, perhaps, if the budget does not collapse along the way. And as part of the SLS program, Launch Complex 39-B has been returned to the "clean pad" configuration it once had, back when the Saturns were doing their heavy lifting. The FSS and the RSS are no more. Gone forever, never to return. But there remains at least one piece of the equipment we furnished and installed, way back when. The North Fucking Piping Bridge. Yep. Still sitting right there, right where we originally put it on its bearing pads and torqued down the nuts on the anchor bolts. A two-hundred thousand dollar contract credit, in exchange for nothing. Nothing at all. Good work if you can get it, I suppose. And at this remove in time, about all I have left to say about any of it is that I sincerely hope and pray that all of the thieving NASA principles involved with stealing that sum of money from Sheffield Steel are enjoying the weather in hell. Assholes.

Return to 16streets.comACRONYMS LOOK-UP PAGEMaybe try to email me? |